“Europe in anything other than the geographical sense is a wholly artificial construct.” Sobering words, especially coming from Margaret Thatcher in her book Statecraft. In the 1980s, the Iron Lady dragged Britain out of the economic crisis, giving the country back its sense of a world power. To this day, Great Britain has its own, dissenting view in its dealings with EU institutions.

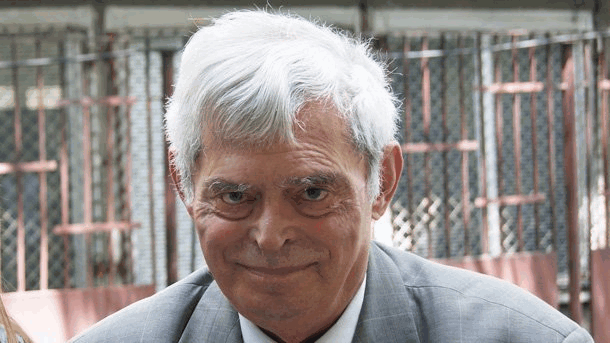

For Bulgaria, however, membership of the EU and NATO were the two ultimate goals that kept the country steadily on the road to democracy, whatever the obstacles along the way. In its post-1989 years, Bulgaria has on more than one occasion doubled back, the result of the irresistible pull of nostalgia, yet it was this aspiration of Bulgarians – to join the elite European club of nations – that has helped the nation outgrow this cast of mind and lead it along the road to democratic development. So, the invitation to join the European family of nations divided Bulgaria into Еuro-optimists and Euro-sceptics. Prof. Nikola Georgiev from the St. Kliment Ohridski  University, Sofia was among the Еuro-sceptics:

University, Sofia was among the Еuro-sceptics:

“My life experience has taught me that when a rich man offers a poor man partnership and the rich man promises the poor man something, the poor man is bound to be on the losing side. Such are the rules of the so-called market economy – relations such as these can never bring an equal profit to both sides. There is no way this could happen… I don’t know what being a Euro-sceptic means – it is a word that is unclear to me, as is the word “Europe”. But let me say it again – we were placed in a position in which we can only repeat the words of Aleko Konstantinov’s Bai Ganyo – “We are European, though not all the way”.”

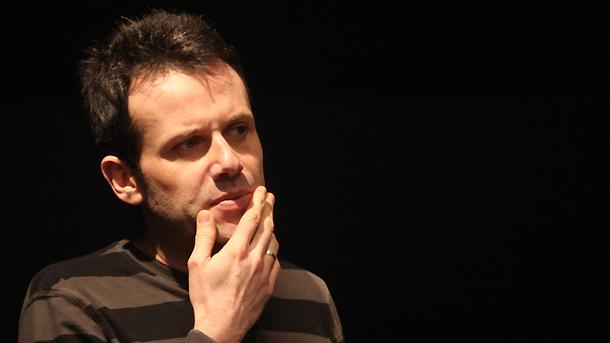

However, Euro-optimists like theater director Yavor Gardev answer back:

However, Euro-optimists like theater director Yavor Gardev answer back:

“Our marginal position with regard to Europe – our constant hovering on the outskirts, now inside, now outside, our having been forced to live outside this community for a long period – this has always placed us in a problematic position. From now on that will change.”

Ten years had passed from the end of 1995, when Bulgaria applied for membership of the EU, till 25, April 2005, when Bulgaria’s accession treaty was signed in Luxemburg, to come into effect on 1, January 2007. Two governments had been crucial to this historic event: that of the Union of Democratic Forces with Prime Minister Ivan Kostov, which laid the foundations of the process of accession negotiations and set down the direction and the pace, and that of Simeon  Saxe-Coburg-Gotha who actually signed Bulgaria’s accession treaty:

Saxe-Coburg-Gotha who actually signed Bulgaria’s accession treaty:

“On 25 April Bulgaria made its political comeback to the family of European nations to which it had always belonged. With its history going back thousands of years, its unique culture and deeply-rooted European values, my country shall make its contribution to the common good, to the cultural diversity and development of the EU. I would like to make this treaty a gift to the young generation of Bulgaria, as it is they that shall bear the burden of European integration, promote community ideals and work towards the unity, peace and success of Europe in the 21st century.”

Bulgarians had to “bite the bullet” and pay the cost of their EU membership – with the decommissioning of four Kozloduy nuclear power plant reactors, as well as other severe terms that were set down in the process of the accession negotiations. We accepted monitoring under the Cooperation and Verification Mechanism over flaws in the sphere of justice, the fight against corruption and organized crime. Even though the country was expected to join the Schengen area in 2010 that is still a matter for the future. Once Bulgaria became an EU member, the country started to change, absorbing funding from the European structural funds. The EU has given us the most important thing of all – the right to free passage, to living and working in any other European country, and to our children obtaining a European education. As a token of encouragement, in 2000, seven years before its EU accession, Schengen visas for Bulgaria were dropped.

English Milena Daynova

Bulgaria had no Prague Spring, no Tender Revolution, no Solidarity movement, nor huge dissidents like Havel and Wałęsa. The main reasons are the psychology of the Bulgarian people and the repressions against the intellectual elite..

Reciting his poem An Interview in the Whale's Womb, Pavlov went on to say: „To enter the whale's womb you should prove you've got worth. There is 'worth' control… There I first met Valery Petrov, and say, Boris Hristov met me…”..

The Other Bulgaria – these were the thousands of Bulgarians outcast abroad after the pro-Soviet coup d’etat on 9 September 1944. Scattered around the globe, they carried the image of their motherland, its controversial past, tragic present..

+359 2 9336 661