For the past four years, Neli Itskova has been teaching history and geography at the Bulgarian Sunday School “Peyo Yavorov” in Brussels. She says it took a long journey to fulfil her dream of working with children.

Itskova graduated in pedagogy from Shumen University “Bishop Konstantin Preslavski.” Immediately after receiving her teaching degree, she began looking for a job in schools in her native Razgrad region, but luck was not on her side.

“In the years I graduated—2013, 2014, and 2015—it was almost impossible to find work as a teacher,” she says. “I asked at the school in my home village of Rakovski, Razgrad, but it was very difficult to get a teaching position for someone without experience. So I started working in a factory making cables for export. I spent some time in manufacturing, and then a few months as a shop assistant.”

In 2020, Neli decided to look for professional opportunities abroad. She chose Belgium, where her parents had been living for years, knowing she could rely on their support while pursuing her dream of becoming a teacher. She arrived in Brussels just hours before the borders closed during the first wave of the pandemic.

“I arrived here in March 2020. I remember the exact date—13 March—because the borders closed the following day. Everything shut down. That period was extremely difficult for me personally. With the whole world in lockdown, I didn't know which way to turn. I had no idea how to move forward. For several months, I couldn’t even register in Belgium. So 2020 was a tough year. Things only began to improve the following year. I started working as a cleaner. I spent nine months cleaning—the only job I could find to help me get the papers I needed. I had to start absolutely everything from scratch,” the young woman recalls.

After this period of trials and hardships, fate gave Neli Itskova a break. In 2021, a teaching position became available at the Bulgarian Sunday School attached to the embassy in Brussels, and she started working there.

“People around me told me, ‘You can apply to the Bulgarian school. We've heard they're looking for teachers.’ But I kept telling myself that I had no experience. Yes, I had a degree, but I’d never had the opportunity to work with children in practice. Knowing something in theory is one thing, but actually standing in front of a class is another—there’s a huge difference. I remember it was April, and I spent three days contemplating whether to send my CV and cover letter. I wrote them, but they just sat on my computer for three days because I was so unsure of myself. I kept repeating that I had no experience. Eventually, I found the courage to email them. That same day, Ms. Valentina Naydenova from the Bulgarian school called me. She introduced herself, and we had a chat. Thanks to her, I was given a chance and started at the Bulgarian school, initially with just two teaching hours, which gradually increased.”

“Being a teacher nowadays is both a challenge and a test,” says Neli Itskova. “A teacher must be not only an educator, but also a psychologist.

What I’ve observed over the past four years at the Bulgarian school is that children in grades 5 and 6 are more cooperative. They pay attention, listen, ask questions, and are well-informed. But everything changes completely in Years 7 and 8. We come back from summer break, and I see how much they’ve grown. I notice changes in their character; their interests are entirely different. You have to be very skilled, almost like a magician, to hold their attention. They are completely absorbed in their phones. They are physically present, but their minds are miles away. It becomes much harder to keep them focused in grades 7 and 8. Later, in grades 9 and 10, things settle down a bit. They begin to understand that they need to make more serious decisions about their future studies. Some students even tell me in advance that they plan to return to Bulgaria and that they will need good grades in subjects such as history and geography,” says the teacher.

Is the work more challenging for educators who teach bilingual children?

“I don’t think so. In fact, I'd say it's an advantage. Sometimes, when we talk about Bulgaria and at the same time another country or geographic feature comes up, they already know about it. They’ve learned it in their own schools—French or Flemish. Sometimes the children even give me more information,” says Itzkova.

How do you teach Bulgarian history and geography to children growing up far from the country?

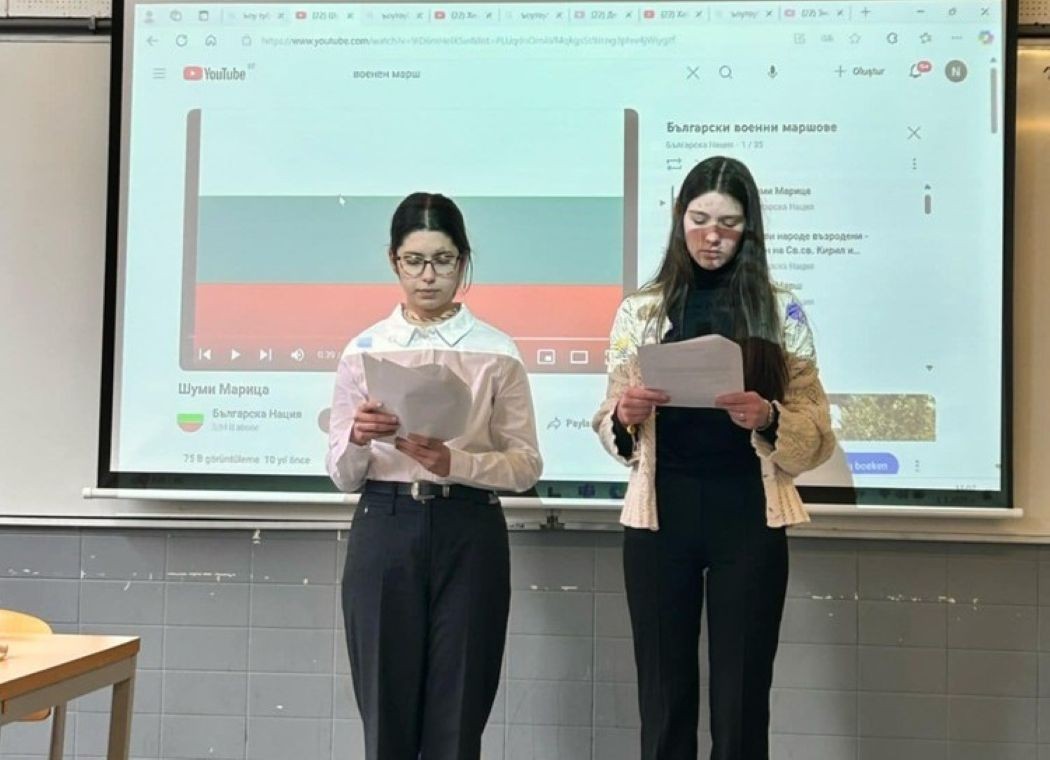

“In fifth grade, they are very interested in Bulgarian history. They want to learn interesting facts about the Bulgarian khans. That curiosity continues in sixth grade. But in the seventh and eighth grades, they lose interest a little, saying things like, ‘I don't really need this, but my parents make me.’ Later, these children realise how important it is to know Bulgarian history and understand their roots. Sometimes they find history far more interesting than geography. We argue over certain topics; they are curious and look up information online. When we reach the period of the Bulgarian National Revival, they are fascinated. I try to recreate the atmosphere from centuries ago. Instead of writing on sand, we write on salt with a stick. In fact, Sunday schools are a modern version of the old monastic-style schools. Today, many Bulgarian children are born outside Bulgaria, and thanks to Sunday schools, they continue learning Bulgarian, as well as the history and geography of the country. The exercises we do leave a lasting impression, and the children especially enjoy writing with pen and ink,” says Neli Itskova.

She is happy with what she has achieved so far and continues to gain professional experience by working at the Bulgarian Sunday School and as an assistant teacher in a Belgian school.

“Gradually, opportunities began to open up for me. There is still much to learn, but I am satisfied with what I have achieved in recent years. Of course, I still have a long way to go, because I am only at the beginning of my journey,” says the Bulgarian teacher in Brussels at the end of the conversation.

A talented pianist and renowned piano teacher, Rossitza Banova has been teaching in the USA and Asia for almost three decades . She has performed in Austria, Hungary, Poland, the Czech Republic, Spain, France, Greece, Russia, China, Vietnam and..

Erica Perales came from faraway Argentina and managed to conquer the hearts of the participants in the 1 st Festival of Bulgarian Folklore Ensembles Abroad . During the event in Veliko Tarnovo, she performed in a unique way one of the..

A successful soloist and renowned teacher, Bulgarian violinist Devorina Gamalova has lived in London for more than three decades . She was born in Bulgaria's town of Gabrovo, to a Bulgarian father and a German mother from Dresden. She studied in Ruse..

+359 2 9336 661