“The museum – unexpected, open, shared” is an unorthodox exhibition which turns the idea of a museum as a place which stores memories on its head. And instead of telling one story with the help of exhibits, viewers are able to trace one story by looking at just one exhibit.

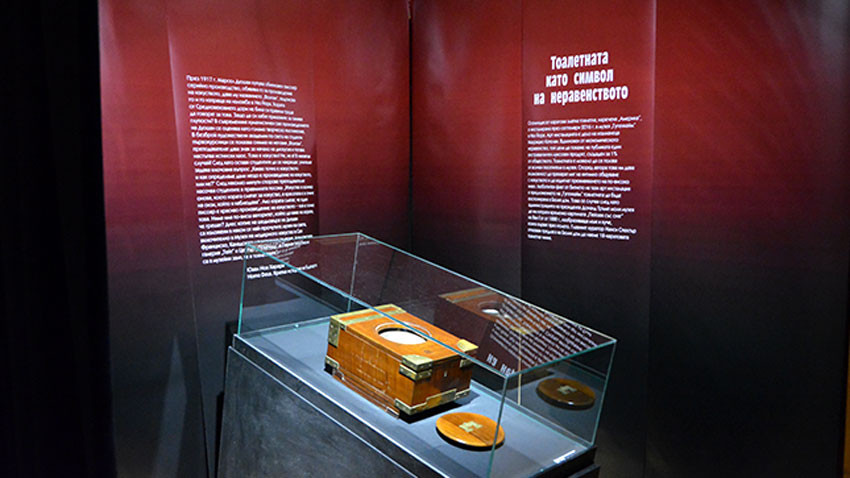

The exhibition on at the National Museum of Military History, which is on the “Plovdiv- European capital of culture, 2019” programme, features just nine exhibits, but they each lead us in different and unexpected directions. And the first direction is traced by… the latrine belonging to Prince Alexander of Battenberg:

“We were provoked into showing this exhibit, this “character” in a story that is 100 years old,” says Slaveya Surcheva from the National Museum of Military History. “In 1917 renowned artist Marcel Duchamp bought a urinal and presented it at an exhibition. Asking the question: “Which object is a work of art?” he started a discussion that has continued to this day. The “urinal” controversy is still the object of study at art academies around the world, and lecturers are still asking their students the same question. And the answer given by culturologists is that even a latrine can be art, as long as the person looking at it sees it as art. That is what we have tried to do – prompt visitors to use their own judgement and say what is art and what is not. We tell other stories as well, among them, the Turkish toilet by artist David Cherny as a symbol of Bulgaria during the Czech Presidency of the Council of the EU.”

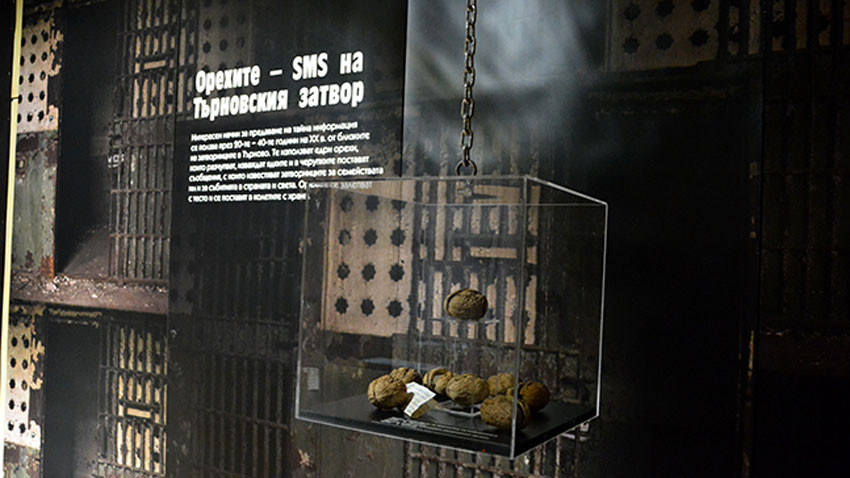

There are other fascinating things that can be learnt from the exhibition. For instance – how the precursor to text messages was born in the 1920s, when relatives of the people incarcerated at the prison in Veliko Turnovo started sending them halved walnuts with little notes inside.

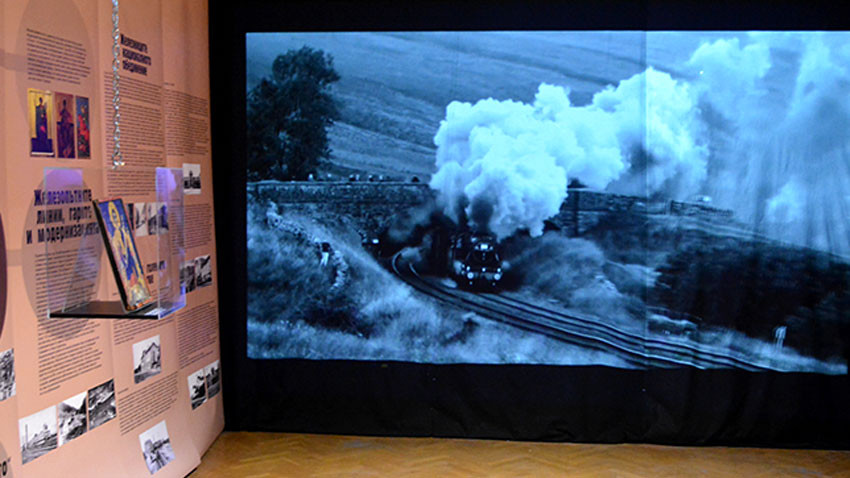

Or how a woman decided to confront the “devil’s invention” – the train, an icon of St. Dimitar in hand, but fainted at the station.

Or how the owl – otherwise a symbol of death – helped save lives.

“During World War I an owl came flying up to a Bulgarian regiment on the southern front,” Slaveya Surcheva says. “The soldiers saw there was a note in French attached to it that a big French offensive was to begin a few days later. This is a story that has not yet been clearly explained – was the note written by the French who wanted to warn the Bulgarians, or was it written by a captured Bulgarian soldier and addressed to his brothers-in-arms?”

Another wartime story brings to mind a fundamental question: which is worth more – ideological fortitude or a human life:

“During the cold war a fire broke out on board a Russian nuclear submarine,” Slaveya Surcheva goes on to say. “When they saw this drama unfold, a Canadian ship responded with the idea of helping the people in distress. But the Russians refused their help, probably for ideological reasons. Then a Bulgarian ship responded to the SOS and saved many human lives. As a sign of gratitude the Bulgarian crew received a watch which is on display at the exhibition.”

Other fascinating exhibits include the camera belonging to Dimitar Dimitrov, fully functional and made out of a piece of pencil, a handbag clasp, a torch handle and other odds and ends; the cork for fizzy drinks invented by the man who created the first Bulgarian airplane Assen Yordanov; the fur coat belonging to aviator Simeon Petrov who flew in an open airplane; the legendary Enigma encryption machine, on which visitors can encode their own messages in the Cyrillic alphabet.

Other fascinating exhibits include the camera belonging to Dimitar Dimitrov, fully functional and made out of a piece of pencil, a handbag clasp, a torch handle and other odds and ends; the cork for fizzy drinks invented by the man who created the first Bulgarian airplane Assen Yordanov; the fur coat belonging to aviator Simeon Petrov who flew in an open airplane; the legendary Enigma encryption machine, on which visitors can encode their own messages in the Cyrillic alphabet.

The exhibition is on in the building of the old Plovdiv airport until 14 July.

The Bulgarian minority in Romania marked a significant event with the official opening of the Bulgarian Inn in the village of Izvoarele (Hanul Bilgarilor), Teleorman County (Southern Romania)- a locality with Bulgarian roots dating back over 200 years...

The 14th edition of DiVino.Taste, Bulgaria’s leading forum for wines and winemakers, will take place from 28 to 30 November at the Inter Expo Centre in Sofia. Over 80 producers from all wine regions will participate, offering tastings of around 600 of the..

Minutes before the second and final reading, at the parliamentary budget and finance committee, of the state budget for 2026, the leader of the biggest party represented in parliament GERB Boyko Borissov halted the procedure and sent the draft bill..

+359 2 9336 661